As I enjoyed the festivities over Fourth of July weekend, I could not help but notice that my eight-year-old son was not quite himself. I did not have to pull teeth to get it out of him: it was literally because he was having some teeth pulled the following week. “Preventive orthodontic treatment” is what they call it. Remove teeth now that may become problematic later in the hopes that this procedure will avoid — or at least limit — the need for future orthodontic treatment.

To an adult who has gone through the discomfort and the cost of years of braces on their teeth, this preemptive procedure makes sense — a little bit of pain now for a lot of pain saving later. But to a child, all that matters is the pain now part, as the benefits are impossible for him to comprehend and appreciate. As the date was growing closer, so too was his anxiety. As the music continued to play at the picnic, Tom Petty summed it up best, “The Waiting is the Hardest Part.”

Over the last few years, investors have also been dealing with the difficulty of waiting for inevitable — or at least seemingly inevitable — events to occur. The possibility of Greece exiting the Eurozone has weighed on the minds of investors for over five years now. A shift in Federal Reserve policy has been a prominent investor concern since the U.S. economy and stock market started their respective recoveries in 2009.

While Greece may or may not leave the Eurozone, the Federal Reserve will certainly increase interest rates at some point in the future. Regardless of the timing of these eventualities, like my son and his oral surgery, we believe that the waiting will prove to be the hardest part.

Greece: More Drama than Tragedy

While the uncertainty is enough to spook investors in the short-term, the long-term damage of an exit by Greece from the Eurozone would likely be limited outside of Greece’s borders. Their economic footprint is small globally — 0.3% as of 2014, according to the International Monetary Fund, the same percentage as Iraq, Algeria, and Kazakhstan. Even within Europe, only Cyprus, Macedonia, and Malta send more than 2% of their total exports to Greece according to Oxford Economics.

European banks have much less exposure to Greek debt than they did in the past. Standard & Poor’s estimates that European banks have cut their exposure by 76% from €175 billion at the peak in 2008 to €42 billion currently. Banks in the United Kingdom and Germany are the most exposed, but Greek debt represents just 0.6% of the German banking sector and just 0.4% in the U.K.

European governments are the largest holders of Greek debt, but the most exposed countries are Slovenia and Malta where the exposure represents just 3% of GDP, according to Bloomberg. Germany is the largest holder in terms of total debt, but it is just 2.4% of their GDP.

Former Eurozone problem countries Ireland and Spain are actually seeing their economies turn around. Ireland’s GDP grew by 4.8% in 2014 — the fastest rate of growth in Europe — while Spain’s economy grew last year for the first time since 2008 (+1.4%).

As a result, the risk of contagion caused by a Greek exit from the Eurozone appears low compared to five years ago.

Rising Interest Rates Affect Stocks & Bonds Differently

There is no arguing that historically low interest rates have helped to fuel what is now a six-plus-year bull market in U.S. equities. However, it would be incorrect to imply that the removal of low interest rates via a change in Federal Reserve monetary policy would cause the U.S. stock market to change course. Higher interest rates are a signal that the economy is improving, which is a positive for equity investors. Rather than which direction interest rates are trending, equity investors should be more concerned about the level of interest rates. According to The Leuthold Group, rising interest rates have not caused serious trouble for the stock market until the 10-year Treasury yield moves beyond 6%. Given that it currently sits at 2.3%, it will take an extended period of rising rates before we get close to that level.

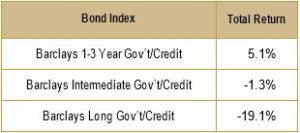

As for bond investors, they should be most interested in the speed at which rates rise. A slow and gradual period of incremental rate hikes — which the Fed has clearly designated as its plan — will not be that damaging to the values of bonds, assuming you are not taking too much interest rate risk with your fixed income portfolio. Even in a worst-case scenario where bond yields move upwards quickly, the downside of bonds is significantly less than that of stocks. From June 1980 to September 1981, the 10-year Treasury yield climbed from 9.5% to 15.7% in just over a year. During that time, short-, intermediate-, and long-term bonds performed as follows:

As you can see, the significant damage was limited to long-term bonds due to their high degree of interest rate risk. Intermediate bonds were close to flat. And short-term bonds actually gained ground as the benefit of being able to invest the proceeds of maturing bonds at higher rates outweighed the decline in value.

Despite what happens (or doesn’t) in Europe or at the Federal Reserve, we expect that the long-term returns provided by stocks and bonds will be worth the wait.