With my oldest child starting kindergarten in the fall, I am beginning to get nervous about being called upon to help him with his homework in a few years. I should be fine for the near future, as I have my ABC’s and 123’s down cold, but when he starts getting into geometry and chemistry, I may be in trouble as I have certainly forgotten more than I remember. However, I am supremely confident that when he reaches the junior high science lab, I will be able to rattle off the definition of osmosis like I learned it yesterday. It’s quite strange, but for some reason, I can recite verbatim the definition of osmosis–the diffusion of water through a semi-permeable membrane–despite learning it over 20 years ago. Even more bizarre, I’m not the only one, as the friends I stay in touch with from that class possess the same ability. Osmosis owes you one, Mrs. Firpo.

Capital vs. Labor

Fortunately, for the sake of my employment and our clients’ assets, I retained significantly more knowledge from my economics classes. One of the key lessons that was beaten into my brain by various professors is the fact that corporate profit margins are mean reverting (i.e. the tendency of data to return to its long-term average) because of the constant competition between capital and labor for their respective share of the profits. As profit margins increase, workers demand a bigger slice of the profit pie, and as margins decrease, owners cut labor costs to drive them back up.

I am not the only investment professional who recalls this particular lesson. Corporate earnings have been recovering from the last recession since the second quarter of 2009, and the recovery has been a swift one, as the S&P 500 Index should set an all-time high in earnings per share with the conclusion of second quarter 2011 earnings reports. Yet over the past two years, many investment professionals have been questioning the sustainability of the earnings recovery due to the fact that profit margins are approaching the high end of their historical range. If what we have been taught holds true, the margins should follow their mean-reverting tendency and decline over time, thereby lowering corporate profits as well.

Corporate Profit Margins

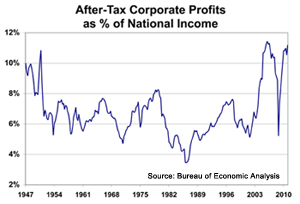

Going back to 1947, you can see that corporate profit margins float inbetween a range of about 3.5% to 11%, supporting the theory that they are mean reverting. The current level (as of March 2011) is 11.2%, suggesting that we are indeed nearing the top end of the historical range. However, it is worth focusing on the right side of the chart from about 1986, when margins bottomed at 3.5%, to the present day. As you can see, the trend in profit margins since then is clearly up. Many economists would argue that this is due to the increased leverage in the economy since that time, and that fact is certainly true and definitely a factor. And while the economy is unlikely to continue to accumulate debt at the same rate as it has over the past twenty-five years, there are other factors that support the idea of sustainably higher profit margins.

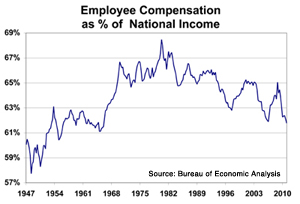

First, technology has undeniably improved by leaps and bounds over the past twenty-five years, which has led to tremendous gains in business productivity and less demand for labor. Second, labor is less powerful than it used to be and consequently has less sway over ownership. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there were actually three million fewer union members in the U.S. in 2010 than in 1983 despite the fact that the number of non-farm workers has increased by over 40 million since then. And lastly, there is the effect of increased globalization in recent years, which has allowed U.S. companies to outsource production to countries with cheaper labor forces. As the adjacent chart clearly shows, the result of all of this has been a declining share of the profit pie for U.S. workers since 1980.

Whether this trend of elevated profit margins and shrinking employee compensation rates is fleeting or sustainable remains to be seen, but there is sufficient evidence to suggest we may have entered a new paradigm for corporate profitability sometime in the last 25 years. Perhaps we will be able to settle this issue when they (re)write the economics textbooks my son will use in college, but for now, our bet is on equities and continued corporate earnings growth.