One of the basic principles of economics is the substitution effect. It states that consumers will find a substitute for a good if that particular good becomes too expensive. For example, if you go to the store and find that the steak you planned to cook for dinner is suddenly $20 per pound, you will likely change your mind and substitute chicken onto your menu to save a few bucks. Clearly, beef and chicken are not identical products, but in the sense that they are both meat and sources of protein, they act as reasonable substitutes for one another.

Traditional bonds have become very expensive, which means that they offer very low interest rates as a result; bond prices and interest rates move inversely to one another. So you as an investor should be searching for income-producing substitutes for bonds in your portfolio just as you would with overpriced products and services.

In this white paper, we will explore various types of income-producing assets to find the best candidates to act as substitutes for traditional bonds in your portfolio, as you and investors around the world seek to replace the income and yield lost to historically low interest rates. Unfortunately, there are no free lunches in finance—any attempt to pick up additional yield also involves taking on more risk—so we will explore the risks involved in investing in each potential substitute as well to help you figure out which are the best fits for your portfolio.

Extending Duration Risk: Long-Term Bonds

One way to increase the yield of your portfolio is to simply extend the duration of the bonds that you are holding—effectively swapping short-term bonds for intermediate-term bonds or intermediate–term bonds for long-term bonds. In a normal market environment, the yield curve is positively sloped, meaning that you are paid a higher interest rate for longer-term bonds than shorter-term bonds. Intuitively, this makes sense as you should be rewarded for locking up your money for a greater period of time.

The problem with this approach now is that it is likely that we are somewhere near the end of a 32-year steady decline in interest rates. Interest rates move inversely to bond prices, so when the cycle does end and interest rates begin to rise, bond prices will decline. And it will be long-term bonds that suffer the most as bonds with longer maturities are more sensitive to interest rates. If you hold a bond that pays 3% per year in interest, that bond is no longer as valuable when interest rates rise to a point that you can buy a similar bond that pays 6%. If your 3% bond matures next year, it is not a big deal as you will be able to reinvest your principal at 6% when it matures in short order. However, if your 3% bond matures in 20 years, it is a big deal as your security will be paying below market rates for a very long time. That’s not attractive to investors, so its price will fall much more than the 3% bond that matures next year.

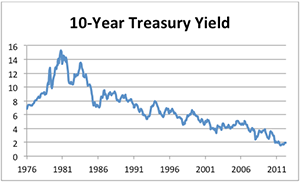

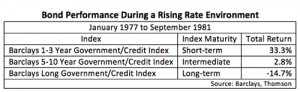

From the start of 1977 to the end of September 1981, interest rates rose to high levels and in a relatively short amount of time. During this near-five-year period, the yield on the 10-year Treasury bond increased from 6.8% to 15.8%. As a result, this time period provides an excellent historical stress test for bonds and how they perform during a rapidly-rising interest rate environment.

Interest rates have been in a downward trend since late 1981.

The above table illustrates how short-, intermediate-, and long-term bonds performed during this period. As you can see, short-term bonds fared the best as bondholders were able to quickly reinvest these bonds at higher rates as they came due. And as expected, long-term bonds performed the worst as their prices fell as a result of being locked into below market interest rates for a very long time.

Given where we currently are in the interest rate cycle, we view it as much more likely that interest rates will increase over the coming years than continue to fall or remain stable. As a result, we do not view it as a prudent risk to substitute long-term bonds into your portfolio to boost yield. While such a move would improve your yield while interest rates remain near their current levels, any meaningful increase in rates would likely cause losses to long-term bonds that would far exceed their current yield advantage.

Extending Credit Risk

Aside from extending duration risk to increase yield (which we do not advise), you can also extend credit risk. Credit risk is the risk that the entity that you loan money to fails to pay your principal and interest back in full. As they say, the return of your principal should be more important than the return on your principal. As a bond investor and lender, you receive a higher interest rate as compensation when you lend to riskier borrowers, so let’s look at some prudent credit risks we can take now to improve the yield on your portfolio.

Emerging Market Bonds

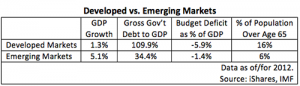

Emerging market bonds are bonds issued by the governments of non-developed economies—examples of which include most nations within Latin America, Asia (excluding Japan), Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. Traditionally, these bonds have been seen as higher risk than the bonds of nations with developed economies—like the United States, Western Europe, Japan, Canada, and Australia—because defaults occurred more frequently in emerging economies. However, in the current economic environment, many emerging market economies possess better fundamentals than heavily-indebted developed nations with aging populations.

It is commonly understood that emerging economies enjoy higher economic growth rates than developed nations, but what is often overlooked is that they also possess lower amounts of debt, smaller budget deficits, and younger populations relative to developed nations, as summarized in the adjacent table.

Yet, despite these facts, emerging market debt is still treated as if it is substantially more of a credit risk than the debt of developed nations. As a result, it yields substantially more. Given that investors are treating emerging markets like the high credit risk it used to be (while at the same time treating the bonds of highly-indebted developed nations as risk-free), we view emerging market bonds as a prudent way to increase the credit risk in your portfolio to achieve more yield. Granted as long as the market views emerging market bonds as high risk (right or wrong), these securities will involve higher volatility and potential for loss than the bonds of developed nations, but it can certainly be argued that they are less of a credit risk, which is something these emerging economies may be able to prove over time.

High-Yield Bonds

Formerly known as junk bonds prior to their rebranding campaign, high-yield bonds are simply bonds issued by companies with less-than-stellar creditworthiness. In short, they are corporate bonds with a high degree of credit risk. As a result, they pay higher yields than bonds from companies in better financial shape.

Despite a tepid economy in the United States, corporations are currently in very strong shape relative to where they have been historically, and this fact even extends to companies in the high-yield space. According to the bond rating company Fitch, the default rate of high-yield bond issuers was 1.9% in 2012, well below the historical average of 4.9%. They expect a similar default rate for 2013.

High-yield bonds currently offer significantly higher yields than both government bonds and bonds issued by investment-grade (i.e. financially strong) corporations. Of course, they should, because high-yield companies will always be at a greater risk of default — despite the low number of incidents recently. But because of the strength of Corporate America, the low number of defaults, and credit spreads that are in-line with their long-term average (suggesting fair valuation), we view high-yield bonds as a prudent way to increase credit risk in your portfolio to earn better yields.

While the risk statistics of high-yield bonds fall in between those of traditional bonds and stocks, they are much closer to stocks in terms of volatility and potential for loss. For example, in 2008 stocks, as measured by the S&P 500 Index, lost -37.0% while the bond market, as measured by the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, gained 5.2% thanks to its high allocation to high-quality, traditional bonds. High-yield bonds, on the other hand, declined -26.4% that year as measured by the Merrill Lynch High Yield Master II Index. And since September 1986, high-yield bonds have been much more correlated to stock price movements than bond price movements (0.58 to 0.24), so it is important to understand what you are getting into before substituting high-yield for traditional bonds in your portfolio.

Leveraged Loans

If high-yield bonds have some allure but you remain concerned about the level of credit risk you’re taking, leveraged loans may be the answer. As with high-yield bonds, leveraged loans are typically issued to companies with less-than-stellar credit quality; however, these loans are structured so that they are higher up on the capital structure than high-yield bonds. In the event of a default, the recovery rates on these loans are higher than with high-yield bonds, because leveraged loan investors are paid first.

Another nice feature available with leveraged loans is their floating-rate structure, which means that their interest rate is variable and will change with market interest rates. This removes interest rate risk to a large degree as the bond’s interest payments will rise with interest rates.

Leveraged loans still involve risks similar to those of high-yield bonds in that they are loans afforded to companies which may not be in a position to pay them back; however, given their senior claim status in the event of default and their floating-rate structure, they are slightly less risky than high-yield bonds. Of course, that means they yield a bit less as well, but their yields still remain high enough to boost the yield of your portfolio if you replace some of your traditional bonds with leveraged loans.

Accepting Equity Risk

You don’t have to limit yourself to extending the credit risk of your bond portfolio to help improve the income yield of your portfolio. There are plenty of income-producing securities within the equity space that are paying significantly more than traditional bonds in the current market environment. While you would be accepting significantly more downside risk by substituting income-producing equities for bonds, it is worth considering, because income payments from equities do a better job of keeping up with inflation than fixed income payments from traditional bonds.

From 1960 to 2011, dividends on the S&P 500 Index grew at an annualized rate of 5.4% versus inflation of 4.1% annualized over the same period. As for traditional bonds, their interest payments did not grow because they are fixed—hence the term fixed income. Over that 51-year period, the income component of stocks stayed ahead of inflation by 1.3% per year annualized while bond interest lost 4.1% in purchasing power each year. By replacing some of your traditional bonds with income-producing equities, you would, in a sense, be exchanging one risk for another—more risk of loss in the short-term for less inflation risk over the long-term. Given that we view inflation as a significant long-term risk given the amount of monetary stimulus we are witnessing from central banks around the globe, we see that as a prudent risk to take, so let’s look at some income-producing options in the equity space for your consideration.

High-Dividend-Paying Stocks

The current yield on the S&P 500 Index is 2.2%—better than the yield on the 10-year Treasury bond but still nothing to get too excited about. However, you don’t have to settle for the market dividend rate; rather, you can focus on companies with above-average dividend yields.

One common investor mistake in seeking out high-dividend paying companies is to focus solely on the yield—the higher the yield the better. Wrong. Companies often have high yields because the market is pricing stock based on its opinion that the dividend is not sustainable. A stock may sport an 8% yield, but the market may be discounting the price of its stock because it expects a dividend cut in the near future.

A key financial metric to look at to assess the quality and sustainability of the company’s dividend is the payout ratio, which is a company’s total dividends paid in a year divided by its net income. A high percentage suggests the dividend is unsustainable and likely to stagnate or be cut while a low percentage suggests the dividend has room to grow. If this type of basic security analysis is more than you would want to take on, there are numerous mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that run dividend-focused strategies which seek out companies with sustainably high and/or growing dividend payments.

Another bonus of equity dividends is that they benefit from lower tax rates if they are qualified. (For an explanation of dividends that are “qualified,” please visit www.irs.gov/publications/p17/ch08.html#en_US_2012_publink1000171584.) The highest federal tax rate you would pay on qualified dividends under the current tax rate structure is 23.8% whereas the highest rate you would pay on bond interest, which is treated as ordinary income, is 43.4%. If you are looking for a tax-efficient way to earn income that is likely to keep pace with inflation and are willing to take some equity risk, high-dividend-paying companies are worth a look.

Note: The dividends paid by the securities described in the remainder this paper are not qualified and are taxed as ordinary income like bond interest.

Equity Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs)

Real Estate Investment Trusts, or REITs as they are affectionately known, raise capital by selling shares to investors. What they do with the proceeds depends on the classification of the REIT. Equity REITs invest directly in real estate by purchasing property with their investors’ capital.

REITs are subject to special tax treatment in that they are exempt from corporate taxes, but in return for this special status, they are required to pay out at least 90% of taxable income to investors. Most of this taxable income comes in the form of rents from the properties they own. REITs provide an easy way to buy and sell real estate as the portfolio of properties is managed professionally and shares can be sold on an exchange at any time, meaning they have significantly more liquidity than real estate itself.

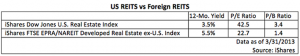

Because of their income mandate to avoid corporate taxes, REITs tend to pay above-average dividends relative to traditional equities. However, we have become concerned with the valuations of U.S.-based REITs, so we recently turned our attention to foreign REITs, which offer valuations that are much more attractive as illustrated by the table below:

REITs involve equity-type risk and possibility for loss. They are also non-diversified in that they only invest in one sector—real estate. Despite the risks, the yields offer significantly more income than traditional bonds, and this is income that will likely keep pace with inflation. Real estate also offers a hedge against high levels of inflation as it tends to perform well, along with commodities, in such an environment. If you are comfortable with the risk, we see REITs as a prudent substitute for bonds in your portfolio to help provide extra yield now as well as an inflation hedge over time; however, we suggest solely focusing on foreign REITs due to valuation concerns in regard to U.S.-based REITs.

Mortgage REITs

Like equity REITs, mortgage REITs raise capital from investors, but instead of buying properties, they buy mortgages. They also use the equity in their portfolios to borrow money short-term so that they can purchase additional mortgages. Like a bank, they look to earn the difference between the interest they receive from their long-term mortgage investments and the interest they pay on their short-term loans. As long as the yield curve is positively-sloped (i.e. long-term rates exceed short-term rates) and the spread between the interest on the mortgages they own and the interest on the debt they owe is wide enough to cover the costs of running the REIT, it is a profitable business model. Such is the environment we find ourselves in now.

Mortgage REITs also employ leverage, which has its pros and cons. On the plus side, the leverage increases the yield by a few multiples. While most mortgages yield in the 3% to 5% range these days, the iShares FTSE NAREIT Mortgage Plus Capped Index, which tracks U.S.-based mortgage REITs, offered a yield of over 11% as of 3/31/2013. The extra yield is due to the leverage in the portfolio. On the negative side comes the risk of investing with leverage. While leverage can improve yield and return when things go well, it can also exacerbate losses when things go badly—a situation that would arise if the yield curve started to invert with short-term rates closing the gap between long-term rates. There is also concern about mortgage rates falling further than their current levels, as such a scenario would reduce the yield spread of mortgage REIT portfolios and cut into their profitability and dividend payouts.

We expect rates to remain stable for at least another year or two. We also expect that long-term rates are more likely to move higher before short-term rates as any Federal Reserve action to push up short-term rates will likely lag the market’s move to push up long-term rates in anticipation of future inflation. Given this outlook, mortgage REITs fit the bill as a substitute for traditional bonds if you are looking to boost the yield in your portfolio. However given the leverage involved in these investments, this is one of the riskier ways to go about increasing your portfolio’s yield, which is why these investments pay 11% currently. Caution is advised as is a sparing allocation.

Business Development Companies (BDCs)

To best understand Business Development Companies or BDCs, think of them as private equity funds wrapped in a REIT structure. In 1980, Congress passed the Small Business Investment Incentive Act, which created BDCs to encourage investment in small, private businesses that are unable to access capital from the financial markets or obtain loans from banks—therein lies the private equity aspect. Like a REIT, BDCs are required to pay out at least 90% of taxable income to investors to avoid corporate taxes. An additional similarity to REITs is that BDCs trade on an exchange, so they provide easy and liquid access to an illiquid and exclusive asset class. Private equity investments typically carry high minimum investments and long lock-up periods.

Older regulations like Sarbanes-Oxley make it difficult and expensive for companies to go public to access the financial markets for capital. Newer regulations like Dodd-Frank make banks reticent to lend. That only increases the pool of private companies searching for non-traditional sources of funding, which increases the pricing and negotiating power of BDCs.

Currently, as a whole, BDCs yield a bit more than high-yield bonds, which they should as you are making an equity investment in the BDC which involves more risk and volatility than lending via a high-yield bond. But the bullish case for both types of securities rely on the same premise—a stable and steadily growing economy. Given that is our outlook, we recommend tying high-yield bonds and BDCs at the hip. As long as neither becomes overvalued and as long as economic growth continues to be positive, both deserve a place in your portfolio as substitutes for traditional bonds if you are looking to increase your portfolio’s yield and you are comfortable with the risks.

Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs)

Master Limited Partnerships are publicly-traded limited partnerships that, like REITs and BDCs, enjoy the benefit of tax-exempt status at the corporate level. To qualify for this special status, they must derive at least 90% of their income from owning, operating, or maintaining energy infrastructure in North America. While many investors assume that MLPs will fluctuate with the price of energy commodities, most are in the business of transportation and storage, so their performance is less tied to changes in energy prices than to the quantity of the commodity that is being transported and/or stored.

The Alerian MLP Index currently yields just below 6%, and as with REITs, MLPs have historically been an effective hedge against inflation. They also provide income-oriented investors added diversification in that MLPs have demonstrated low correlation to other asset classes.

Like everything else mentioned in this paper, MLPs are not without their risks, though, as they do represent an equity investment in a business that benefits from increases in the use of energy in the United States. A slowdown in the economy leading to weakening demand for energy would be a damaging scenario for MLPs. Such was the case from late July 2007 to December 2008, a period that included a recession in the U.S. and a panic sale of risk assets. As a result, MLPs were hit hard, declining over 40% during that time period.

Aside from the risks, MLPs can also complicate your tax picture. Investing in MLPs directly means investing in a partnership. As a result, you will receive a K-1 at the end of each tax year, which requires special reporting on your taxes. Additionally, in our experience with MLPs, the finalized K-1 often arrives after the April 15 tax filing deadline, requiring many MLP investors to file extensions each year. You also want to avoid investing in MLPs in your IRA due to the unrelated business income generated by the partnership, which will require additional forms when you file and the possibility of owing additional tax even though the investment sits in your IRA.

One way to avoid the tax implications with MLPs is to invest in one of the many MLP-focused mutual funds or ETFs that are structured as C-corporations. These funds pay taxes at the fund level, which cuts into your dividend, but this excuses them from having to send you a K-1 each year.

Perhaps the complicated tax issues are enough to give you a headache and convince you to steer clear of MLPs altogether, but if you are willing to deal with them, as well as the additional risks, MLPs offer higher yields, added diversification, and superior inflation protection than traditional bonds. As a result, we think they should be considered as a substitute for some of your traditional bond allocation.

The Concept of Risk Parity

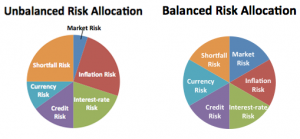

The risk parity approach to investing seeks to balance the various sources of risk across a portfolio. The best way to conceptualize it is through a traditional asset allocation framework, but instead of simply diversifying your exposure to the various asset classes like stocks, bonds, real estate, and commodities, you are diversifying your exposure to the various risks of investing.

The pie charts below illustrate the difference between a portfolio that is balanced in terms of risk and one that is not. In our experience working with investors, the portfolio with the unbalanced risk allocation depicted below is quite common. This often results from investors who are overly concerned about cutting their exposure to stock market risk while ignoring that the subsequently higher cash and bond exposure leaves the portfolio overexposed to inflation risk, interest-rate risk, and shortfall risk (i.e. the risk of running out of assets)—all of which can undo a financial plan just as easily as stock market losses.

Conclusion

Because most investors will naturally overly focus on reducing market risk (due to the common behavioral tendency to avoid losses), the concept of risk parity is a helpful tool in focusing your attention on the full spectrum of risks that can potentially affect your portfolio and your financial goals. Once you do that, you may reach the same conclusion we do—that traditional bonds and their fixed payments combined with historically-low yields will likely prove insufficient in meeting investors’ long-term financial goals. As a result, we strongly suggest considering some substitutes for your bonds to not only increase your yield now but to better balance all the risks that may negatively affect your retirement plan in the long run. While chicken may be an adequate substitute for beef, Top Ramen certainly isn’t.