Last year at this time, we published a white paper entitled “Momentum Investing: How to Gauge the Market’s Opinion of the Future.” (You can read or listen to the paper via podcast here.) In it, we discussed the presence of momentum in the financial markets and why it is valuable information for investors. Although we discussed the reasons behind why momentum works as an investment strategy, we never attempted to explain why momentum exists in the first place.

Before we look at the reasons for its presence in the financial markets, let us return to last year’s white paper for a refresher on what momentum is exactly:

At its simplest, momentum can be defined as the persistence of winning and losing investments. Strong performing investments tend to continue to perform well for a period of time while weak performing investments tend to continue to underperform for a period of time. It is a phenomenon in the financial markets that is well-documented through hundreds of academic studies, yet largely unknown and overlooked by the general investing public. These studies show the presence of momentum in various asset markets—stocks (both foreign and domestic), bonds, commodities, and currencies—and confirm that it has existed in individual stocks as far back as the late 1800s.

There are many reasons why momentum may exist in financial markets. A finance professor would likely argue that the excess returns provided by the momentum factor serve as compensation for some unseen risk in the stocks that have performed well recently. This is the same logic they use to explain why value investing (i.e. purchasing the stocks of unloved and undervalued companies) has outperformed the stock market as a whole over time. In their view, value investors are being compensated with extra return because they are taking on more risk by purchasing companies that are unloved and undervalued for a reason—namely because they are damaged goods or have something fundamentally wrong with their businesses. What exactly the additional risk of investing in stocks with positive momentum is we are not sure, but in theory, this could be one explanation.

Ask a mathematician for the reason behind momentum’s existence in the financial markets, and he or she would likely argue that momentum exists in any random data series. The assumption here is that stock prices are random, which is a debate that is as old as financial theory itself. If we do assume that stock prices follow a random walk, then the mathematician’s point of view can be easily understood by considering the most-referenced random event of them all—the coin flip. We all know that the odds a fair coin landing on either heads or tails on any given flip is a fifty-fifty proposition—a truly random outcome. However, what is most surprising to most people are the long, consecutive runs of heads or tails that inevitably result in a series of coin flips. To illustrate this point, we simulated 100 “coin flips” within a spreadsheet. There were five instances in which the “coin” landed on heads/tails for at least five consecutive occurrences, including a run of nine consecutive heads. In this sense, there is some naturally-occurring momentum within random events, although we certainly do not share the belief that stock price movements and coin flips are one and the same.

We do not purport to have the answers to why momentum exists in financial markets, but like the hypothetical finance professor and mathematician we graciously afforded airtime to above, we have our own theories. We believe that momentum exists in financial markets because of people—at least as a result of their investing behavior. So in the remainder of this paper, we will explore the documented investor behaviors that we believe result in the phenomenon of momentum—the persistence of winning and losing investments in the financial markets.

The Disposition Effect

In 1985, two pioneers in the nascent field of behavioral finance, Hersh Shefrin and Meir Statman, hypothesized that investors have the tendency to sell winning investments too soon and hold losing investments too long.1 They based their belief on the emotional feelings caused by selling a stock at a gain versus at a loss—selling a stock at a gain results in positive feelings while selling a stock at a loss causes negative feelings. Because we humans want to feel good about ourselves, Shefrin and Statman theorized that investors would be quick to sell a winning investment to lock in the gain (and perhaps more importantly the accompanying feeling of success), and at the same time, they would be hesitant to sell a stock at a loss to avoid a feeling of failure and in the hope that the stock would recover its losses and become an eventual winner. They coined the term “disposition effect” to explain this behavior.

What Shefrin and Statman knew theoretically in 1985 was proven empirically 13 years later by Terrance Odean, a finance professor at UC Berkeley. Odean studied the trading patterns in 10,000 retail brokerage accounts and found that investors were, on average, 50% more likely to sell a winning investment than a losing investment.2

In a completely efficient market, investors should quickly recognize the top-performing companies (the winners) and buy them; at the same time, they should recognize the poor-performing companies (the losers) and sell them. But because of the disposition effect, this recognition process does not occur in a timely or efficient manner. In fact, the tendency of investors to sell winners and hold losers creates, in effect, a headwind that delays a stock from reaching its true intrinsic value.

Take for example a company that announces surprisingly strong earnings. In response to the good news, the stock goes up. As a result of the stock going up, many investors sell to lock in their gain and a feeling of success. The selling pressure pushes the stock back down and creates a deviation between the market price and the stock’s intrinsic value based on the company’s higher level of earnings. Because the stock is undervalued relative to the company’s improved prospects, it is set up to outperform going forward.

At the other end of the spectrum, consider a company that announces surprisingly bad earnings. In response to the news, the stock goes down, but there are many investors who refuse to sell their stock despite the bad news because they don’t want to realize a loss and live with the negative feelings that accompany it. As a result, there is inadequate selling pressure to bring the stock price in line with its new, lower intrinsic value given the company’s deteriorating performance. The stock remains overvalued and is set up for a period of future underperformance.

In both examples, it takes time for the market to overcome the disposition effect so that the stock price can catch up with the company’s changed fundamentals. This is why, in part, momentum can often last years at a time.

Herding

From studies of the disposition effect, we know that investors like to avoid the negative feelings produced by the failure of an investment idea. One way they can accomplish this is by never selling their losing investments and the “realization” of their bad trades. However, this is not the only behavior investors rely on to maintain an elevated self-worth.

Another behavior evident in financial markets is herding, which involves following the crowd’s sentiment in making your personal investment decisions. Even if it proves to be the wrong thing to do, the negative emotions that typically accompany an investment loss are muted to a large degree by the simple fact that “everyone else” made the same mistake. Like a herd of animals in the wild, there is safety in numbers.

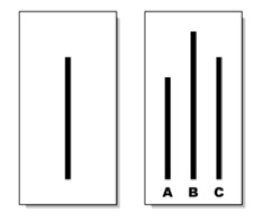

In some well-known experiments from the 1950s, psychologist Solomon Asch recruited groups of students at Swarthmore College to participate in a vision test.3 Each student was shown a series of card pairings like the following:

Then, they were asked which line on the right-hand card (A, B, or C) matched the length of the line on the left-hand card. Without any interference from Asch, participants had a 98% accuracy rate with only one participant providing an incorrect response. However, when the subjects were placed in a group with other students who were instructed by Asch to intentionally provide an incorrect answer, the accuracy rate of participants not involved in the collusion fell to 68%. And 75% of those participants provided a wrong answer to at least one of the questions. If we look to the crowd for answers for a question as simple as this, you can imagine how often we rely on our peers for more complex and esoteric problems like investment selection and portfolio construction.

In looking at the retirement plan of a university with over 12,000 employees4, Esther Duflo and Emmanuel Saez found that, despite the fact that the retirement plan offered four different mutual fund menus from four different fund companies, employees in the same department tended to invest with the same fund company.

While it may not be shocking that co-workers share information about their company retirement accounts, it may come as quite a surprise that your neighbors influence your investment decisions, even the ones you have never met. In a 2007 paper5, Zoran Ivkovich and Scott Weisbenner, in examining the trading patterns of nearly 36,000 households from 1991 to 1996, found that when your neighbors—defined as households within a 50-mile radius—began buying more stocks from a particular industry you were likely to increase your purchases of stocks from that industry as well. So when investors in your area began buying more oil stocks, you were likely to follow suit, whether you consciously realized it or not. Their conclusion was that word-of-mouth communication represented approximately 25% to 50% of the correlation between the stock purchases of households within the same neighborhoods.

When investors herd rather than act independently, the initial result is a flow of assets into a particular type of investment, whether it is a certain asset class, market cap, investment style, geographic region, or sector/industry—whatever investment idea has the herd’s attention at the time. Because of this mass inflow, the prices of these investments rise as the herd grows and buying intensifies, which only serves to attract more members to the herd. After all, not being part of the herd when it is making money can be quite uncomfortable. In the frenzy, other investments get ignored and positive and negative momentum develops (i.e. trends). Ultimately, the buying comes to an end, and a correction or crash typically occurs, sending investors scurrying for the next grand investment idea.

A perfect illustration of this occurred in the late 1990s with technology stocks. Investors piled into the sector not because the companies were performing well—many were losing money and/or had bad business plans—but because everyone else was buying tech stocks. This herding effect led to a huge run-up in the prices of tech stocks, leading to more people joining the herd. This came to the detriment of many other areas of the market as slow-growth, defensive stocks were seen as old-fashioned and sold by investors to free up money to increase their allocation to tech. Ultimately, the run-up in tech stock prices proved unsustainable and a crash in the sector resulted. Meanwhile, those slow-growth defensive stocks that went unloved by investors for years suddenly came into vogue again.

Investors’ tendency to herd explains why momentum can be found in various asset markets as outlined at the outset of this paper, but it also shows why momentum can be found on a more granular level among sectors, sub-industries, and countries. Momentum develops in whatever area of the market happens to catch the herd’s attention. Herding is also the reason why we pay close attention to valuation levels while employing our momentum strategy. While the positive momentum that results from herding can last for years, the trend typically ends suddenly and severely, and extended valuation levels, like we saw with tech stocks in the late 1990s, often provide the first warning signal of a reversal in momentum.

House Money Effect

We showed earlier in this paper how the disposition effect results in investors selling their winning positions too soon as a result of their desire to lock in their gains and that positive emotion that a winning trade produces. Along with positive feelings, a winning trade also produces feelings of confidence that have been shown to influence future trades.

In 1975 Ellen Langer and Jane Roth conducted a study with college students in which they flipped a coin 30 times while asking their subjects to guess heads or tails during each flip.6 They manipulated the feedback in that some students were told, regardless of the actual outcome, that the majority of their guesses were right while others were told that the majority of their guesses were wrong. The students who thought they had high accuracy rates estimated that they could guess the next 100 coin flips with 54% accuracy and half of those students believed they could get even better with more “practice.” Such confidence for a completely random and unpredictable event!

As with (seemingly) predicting the outcome of coin flips, a series of winning trades makes investors not only more confident in their predictive investment powers but increasingly risk tolerant as well. In 1990 Richard Thaler and Eric Johnson conducted an experiment with university students in which they offered wagering propositions using real money.7 When these students were asked to bet $2.25 on a coin flip, only 41% of them accepted the bet. When the same students were initially “awarded” a $15 prize via a rigged game then asked to bet $4.50 on a coin flip, 77% of them accepted the bet. With $15 worth of “house money,” not only did nearly twice as many students choose to gamble, but they agreed to a bet with twice the amount of money at risk as the original proposition.

This is, in part, why we see shifts in market cycles from bull to bear. Investor sentiment and risk aversion vary based on how well their most recent trades fared. And in a bull market, the odds increase that you are experiencing winning trades as the majority of stocks go up. That results in many investors feeling like they are playing with the “house’s money,” which increases their confidence and willingness to take additional risk with future trades. On the “flip” side, in bear markets, the majority of stocks are trading down, and it becomes more likely that you will lose money rather than make it. The opposite of the “house money effect” plays out, and investors become more risk averse. In the coin flip experiment above, when the students were dealt a loss of -$7.50 at the outset, 60% of them declined to bet $2.25 on a subsequent coin flip.

When stocks perform well and investors are playing with house money, the momentum favors more aggressive investments, which is why, in part, more aggressive investments like cyclical sectors, small-caps, emerging markets, and high-yield bonds fare well in bull markets. After the gains turn to losses however, there is typically a shift in investor risk aversion, which results in a momentum shift towards lower-risk investments like defensive sectors, large-caps, and Treasury bonds. This is why we pay close attention to the relative momentum of aggressive versus defensive investments; it provides key information on the level of investor risk aversion and allows us to determine how aggressive or defensive our allocation should be given prevailing market conditions.

The Persistence of Momentum

The disposition effect, house money effect, and herding are simply a few behavioral-based theories for why momentum exists in asset markets. They may be the main reasons; they may not be. And surely there are other factors beyond the scope of this paper. Momentum has suffered from a lack of acceptance in the investment industry because it is not totally clear, despite numerous studies, why it exists. It is often dismissed as an anomaly. However, as noted at the outset of this paper, studies have shown momentum’s presence in asset markets as early as the 1800s8—not surprising considering that, although financial markets were quite different back then, humans, with all of their idiosyncrasies, were still doing the investing. And as long as humans remain present in the financial markets, we are confident momentum will as well.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Notes

- Hersh Shefrin and Meir Statman, 1985, “The Disposition to Sell Winners Too Early and Ride Losers Too Long: Theory and Evidence,” Journal of Finance 40 (3): 777-790.

- Terrance Odean, 1998, “Are Investors Reluctant to Realize Their Losses?” Journal of Finance 53 (5): 1775-98.

- Solomon Asch, 1956, “Studies of Independence and Conformity: A Minority of One against a Unanimous Majority,” Psychological Monographs 70: 1-70.

- Esther Duflo and Emmanuel Saez, 2000, “Participation and Investment Decisions in a Retirement Plan: The Influence of Colleagues’ Choices,” National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), NBER Working Paper Series Working Paper #7735.

- Zoran Ivkovich and Scott Weisbenner, 2007, “Information Diffusion Effects in Individual Investors’ Common Stock Purchases: Covet Thy Neighbors Investment Choices,” National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), NBER Working Paper Series Working Paper #13201.

- Ellen Langer and Jane Roth, 1975, “Heads I Win, Tails It’s Chance: The Illusion of Control as a Function of the Sequence of Outcomes in a Purely Chance Task,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 32 (6): 951-955.

- Richard Thaler and Eric Johnson, 1990, “Gambling with the House Money and Trying to Break Even: The Effects of Prior Outcomes on Risky Choice,” Management Science 36 (6): 643-60.

- Benjamin Chabot, Eric Ghysels and Ravi Jagannathan, 2009, “Price Momentum in Stocks: Insights from Victorian Age Data,” National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), NBER Working Paper Series Working Paper #14500.